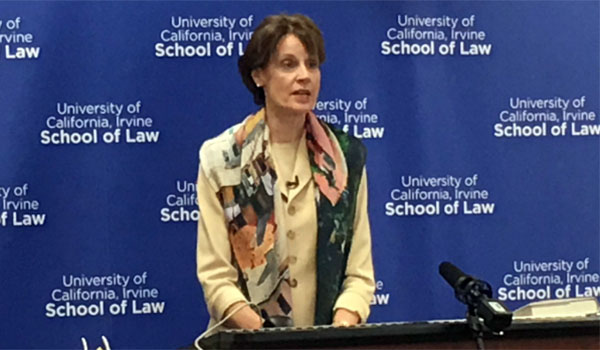

Joan Biskupic on reporting about the U.S. Supreme Court

Recorded at UCI Law event Sept. 14, 2016

Joan Biskupic, distinguished journalist, CNN legal analyst and Visiting Professor at UCI Law (2016-17) shares her observations at a UCI Law event on the Supreme Court justices, the changing demographics of the Court and her quest to answer “Is personal biography judicial destiny?”

-

Joan Biskupic

Legal Analyst and Supreme Court biographer

Visiting Professor

• On the continuing legacy of Sandra Day O'Connor

• On Anthony Kennedy’s evolution on race

• Chief Justice John Roberts’ game of chess

• Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg calls Trump a ‘faker,’ he says she should resign

Featuring:

Podcast Transcript

[Narrator] Welcome to UCI Law Talks, presenting bold perspectives on law from the University of California, Irvine School of Law. Join the conversation on Twitter @UCILaw, #UCILawTalks.

[Henry Weinstein] Good afternoon and thank you all for coming. This year, UCI Law School is a particularly fortunate to have with us, as a visiting professor, one of the nation's leading experts on the Supreme Court, Joan Biskupic, who is seated to my right. Joan has written about the Supreme Court for a quarter century for the Washington Post, USA Today, Reuters. She is a commentator on the Supreme Court for CNN. She is a graduate of Marquette University, as an undergraduate. She has a graduate degree in writing from the University of Oklahoma. And while working as a journalist has a law degree from Georgetown, which she got going to classes at night. As you all know, going to law school just as a full time occupation, is a tough gig, but doing it while you also have another full-time gig. Particularly impressive.

Joan has written three noteworthy books about Supreme Court Justices, starting with her book about Sandra Day O'Connor, how the first woman on the Supreme Court became its most influential Justice. Subsequent to that time, she wrote books on Antonin Scalia and Sonia Sotomayor, both of my copies are at home, so I couldn't show them today. She is currently working on a book on Justice John Roberts, which we hope will appear sometime in the next couple of years. With that I'd like to bring Joan Biskupic to the stage and give you a little gift from the school.

[Joan Biskupic] Oh, thank you. Thank you, Henry and thank you all for being here. I love the reference to the fact that I went to law school at night. As almost everyone in this room knows, it's so hard to be in law school. Occasionally, I'd be driving by Georgetown, where I normally live in DC. And I'd think, "Oh, it would be good to have a Georgetown law degree." And I think, "Oh, I got one." In part it's because it was such a blur.

I was working full-time as a journalist, mainly at the Washington Post at the time. I even hate to say this, but in the middle of it I did have a baby. I remember bringing my daughter, who's now 24, on occasion to the library, because those were the days that you could get stuff online, but you really had to be at the library much more. And trying to keep her quiet as I would maneuver among the law reviews.

Anyway, thank you all for coming today. It's exciting to be here as an actual professor, as a visiting professor, because I have spoken at UCI a couple other times. But I have to say, in just the past four weeks that I've been here it's been so energizing. My students in my class on Chief Justices have just gotten me more intrigued about my research on John Roberts. And being in this wonderful atmosphere has been so inspiring. So I'm glad to be here for this talk this afternoon, but I'm also glad that I'm not about to get on a plane and leave.

As Professor Weinstein said, I've been covering the Supreme Court for 25 years. But I am far from the most senior reporter, among our journalism ranks. Most of us come and we too think we're appointed for life. But what I do, that separates me from my other reporting colleagues, is to do a lot of research that delves deeply into the biographies of individual justices. And explores how they have effected the law of the land.

I want to talk today about some of the themes that have emerged in my three earlier books, and also what I'm trying to do with my new work on Chief Justice John Roberts. But first, some general observations.

The Supreme Court’s demographics have changed dramatically in recent decades. America went from a bench that was all white justices, all male, virtually all Protestant, to a bench that now has three women, one African American, one Hispanic and no Protestants. With Justice Scalia, we had six Catholics and three Jewish justices. If Merrick Garland is confirmed we would have five Catholics and four Jewish justices.

Now, as a journalist who has devoted herself to understanding the lives of the justices, this changing look of the bench has caused me to more broadly focus on the impact of personal biography, on the law and the decisions we all live under. As I sometimes will put it, is personal biography judicial destiny? I found different answers as I've written about the subjects already. Sandra Day O'Connor, then Antonin Scalia and Sonia Sotomayor, and now Chief Justice Roberts.

They've caused me to consider the differences in how biography plays out, the circumstances of birth, the later experiences, and the political associations. Particularly now with Chief Justice Roberts. I've also explored how ground-breaking justices have used their voices once on the bench and how they compare with each other. I think most of you would acknowledge right away that Justices O'Connor and Ginsburg, the first two female justices, are quite different. Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan are themselves very distinct in their jurisprudence.

With Justice Scalia's death this year still on our minds, and affecting so much of the high court, I think I'll start with him. Antonin Scalia grew up in a first generation Sicilian home. He was born in Trenton and reared in Queens. He was an only child. Actually, not only that, he was the only offspring of his generation in this deeply Roman Catholic family.

His mother was one of seven children, his father was one of just two, but in the end, Antonin was not just an only child, there were no cousins. He was it. I thought, "Is that character for me?" "I think so." Then he was first in his class at Georgetown University undergrad and then a graduate of Harvard Law School. He taught for a while at various law schools, serving the longest at the University of Chicago. But here's what I found determinative for him on the substance of the law, he was far more comfortable not in the world of academia but in the executive branch. He loved working for President Nixon then President Ford. And important to many of his decisions over the years, he cut his teeth in Washington in the post-Watergate era.

Scalia developed an antagonism toward Congress. He was constantly testifying on behalf of executive privilege and against disclosure of White House documents. He sparred repeatedly with leading Democrats who were trying to pry information from the executive branch in the post-Watergate era. His authoritarian bent rooted in a very rural oriented father and his Catholic upbringing, as well as his early years in the Nixon and Ford administrations, fostered his concern for the erosion of the executive branch that played out a lot in his opinions. Erosion of the executive branch, erosions on the presidency, those were the ... Encroachments on the presidency, those were elements that certainly emerged in his jurisprudence. And his natural combativeness and alliance, also I thought was ideally suited for the post-Watergate time.

Justice Scalia gave me more than a dozen interviews when I sat with him for this book, and some of the liveliest of those interviews involved his recollections of appearing before Congress. He had a bring-it-on attitude. He'd say things like, "I could have taken them on with one arm tied behind my back." That was so him. And I recalled a version of that audacity after his death, at a Texas hunting resort last February. And the energy with which he had described the passion for the sport to me.

This is Justice Scalia, "It gets me outside the Beltway, it gets me away from the woods, far from all of this." He said in an interview. And on the wall as he spoke was the mounted head of an elk, with an imposing 6x6 rack. Yet Scalia, when he was talking to me, got most excited when he was describing hunting turkey. And as I said, he came at it with almost the same combativeness as he did talking about testifying before Congress.

And he said, "It's more proactive hunting turkey than hunting elk. You're not just waiting. Have you ever heard a turkey gobble?" Now I should say just as an aside, I grew up on the south side of Chicago, I've never even actually held a firearm. So, I have never been hunting turkey. But he said, "It's a very strange sound. Like a wooden rattle. You hear that from far away, and then you make sounds like a hen, to induce him to come closer and closer. Finally he sticks his head up over a log and you have to take your shot, or else you've lost him. You get one shot. If you miss the whole day is ruined." And I thought that really reflected a lot of Justice Scalia. He had that, you get one shot or bring it on kind of mentality.

Now as Antonin Scalia had an inside track to the executive branch, Sandra Day O'Connor, my first subject, and our first woman justice, worked the corridor of power from the outside. She broke in as a civic volunteer and an unpaid party loyalist for Republicans. In time she was elected to the legislature in Arizona and in fact became the first woman to ever serve as a Senate majority leader in any Statehouse nationwide. This is the part of Sandra Day O'Connor's character that I thought really set her apart, her political experience.

During her nearly 25 year tenure on the Supreme Court, she was the only member of the bench that had run for office, run for any kind of significant office. And one of my major thesis of that book was that she came to Washington knowing how to count votes. She arrived in Washington and she had a sense of how to work a room, although certainly her male colleagues didn't think so. A note I found in the Library of Congress archives that Justice William Brennan sent to Thurgood Marshall in 1990, actually began me thinking about O'Connor more in terms of her ability to strategize. And actually set me on the path of that first book.

The Brennan note, written in a criminal case, said, and this is William Brennan talking to Thurgood Marshall. "As you will recall Thurgood, Sandra forced my hand by threatening to lead the revolution." Now I saw that and I thought, how could that be? Brennan was a master strategist who famously could pull five votes out of a hat. But O'Connor, as I found in the papers of retired justices, could give Brennan and then Justice Scalia a run for his money. And she did it with the shrewdness she honed in the legislature.

A few years after her January 2006 retirement, when conservatives had more deeply coalesced at the court, largely because of her successor Samuel Alito. Retired Justice O'Connor told me, she felt that Justices were now dismantling some of her compromised decisions. Now that was her word, they're dismantling. What I asked her, how she felt about that, she said in classic Sandra Day O'Connor form, "Well, how would you feel about that? But then she paused and a little bit later she said, "I'd be a little bit disappointed. If you think you've been helpful and then it's dismantled you'd think, oh dear, but life goes on." Just had all the elements of Justice O'Connor in that.

And I noted in an essay this summer, her opinions have had a resurgence. Since the February death of Antonin Scalia the court has shifted again in its June decision endorsing a University of Texas affirmative action plan. The court majority bolstered an opinion written by Justice O'Connor which many of you probably know well, the [Gruder 00:12:56] opinion. And in a 2003 dispute over affirmative action at the University of Michigan.

Similarly, the court's invalidation of the Texas abortion regulation, a very tough regulation that they struck down by a bare majority, reinforced a decision that Justice O'Connor wrote in 1992 with Justices Kennedy and David Souter. Especially striking was the affirmative action case, because Justice Anthony Kennedy who authored that opinion upholding the Texas race-conscious admissions policy, drew from O'Connor's 2003 decision in the Michigan case. And that was a decision that he had dissented from back in 2003. Yet he highlighted in just last June her emphasis on the way campus diversity prepares students for today's increasingly diverse society. And that leads me to my third earlier subject, Sonia Sotomayor, in my examination of the cultural shifts and political shifts that led to her appointment in 2009.

Now this was a tougher book to write because she was doing her own book at the time, and obviously it's her story. She has a very compelling story. But my approach was to look more at the political history of what led to her appointment. I wanted to tell the tale of how the timing of her generation had helped lift up this daughter of a nurse and factory worker to the highest pillar of the judiciary. It came as Hispanics were emerging as a force in America and she was overcoming her own personal hurdles and walking the fine line between identity and assimilation. As I was putting together that book, on the political history of her nomination, I looked around for tales that no one else would know and that she would not have been eager to share herself in her own book. And I'll briefly share two of those that I think are illustrative.

In the first I want to bring you back to June 2010. Now she's just finished her first term, it's the end of the term party that she's never attended before. And this is a very exclusive affair at the Supreme Court. Only full-time workers are invited. No part-timers, no contractors, no spouses, no family members, as the court allows. For example, at the Christmas party. The festivities are staged in two majestic rooms facing each other. If you've ever been up at the court it's the East and West conference room. Formal portraits of the nation's Chief Justices lined the wall, all men. It's very stuffy atmosphere and it has a certain amount of decorum.

Each year the law clerks write and present these musical parodies, and that's as lively as it gets. But the parodies are really tame, because first of all as we know, expectations of decorum precedent consistency are valued in the Justice's relationships as much as in the law. Now Sonia Sotomayor was about to upset those expectations.

As the skits are ending, and again they're parodies usually of what happened during the term with different clerks playing the roles of different Justices. As they're ending, she springs from her chair, she turns to the law clerks, and she says, she gets them to cue some music on a little portable player. And she says, "Oh, those were all well and fine, but they lacked a certain something." And as music starts playing, it's salsa music, and she starts dancing.

And first she chooses as her partners the law clerks, who it comes to be evident, are in on this diversion with her. The Justices are not. So she starts to beckon them, and I cannot tell you how uncomfortable many of them were, even in retelling it. Because think of those people up there, they're all a button-down group. Any kind of dancing is going to threaten them especially, and then salsa dancing and her doing this.

And remember, this was an event where the clerks perform and the Justices watch. So she beckons first the chief and Chief Justice Roberts is thinking, I don't know exactly what was going through his mind, but he was looking very uncomfortable. He decides to be a good sport, so he gets up to dance briefly. And then she starts looking around, she gets Justice Kennedy to do a little jitterbug thing. Justice Alito who is incredibly awkward in these social situations is resisting her, but then he gets up and say, "All right, all right, all right."

Because by now the whole audience is into this spectacle that people are standing up and they're laughing and they're clapping. And then she says, "Where's Nino?" That was Justice Scalia's nickname. And he's standing on the back wall. For these events he often would position himself at the back wall because he was such an easy target of the parodies. So he would stand in the back and fold his arms, and he's thinking to himself, "There's no way I'm dancing." But she gets to him and he engages in something with her that appears to be enough of a dance.

And then here's the most meaningful. Now I should tell you all, I of course I'm not there. I'm not there, but I have to recreate this because if people pass down to me this was the lucky thing. People in there passed down to me the actual program and then I was able to recreate it through my conversations with justices and other people who were there. So now Justice Sotomayor gets to Justice Ginsburg, and to bring you all back to where we are. This is June of 2010, this is the year of Citizens United. It had been a really, really difficult term, and Justice Ginsburg had just lost her husband of some 50 years. Marty Ginsburg had just died a few days earlier and Justice Ginsburg had made sure she did not miss this end-of-term party. She had missed none of the sittings on the bench, and in fact had even issued an opinion from the bench right after his death.

So she's sitting in this chair and she did not want to rise up for this dancing. She enjoyed it but there was no way she wanted to get up. But Justice Sotomayor whispers in her ear that Marty would have wanted her to get up and dance. So Ginsberg gets up, does a little thing and then she takes her two hands and puts him on Justice Sotomayor his cheeks and mouth, thank you.

So the program closes and the emotions are really strong, because people have just witnessed this, they've witnessed ... First of all, this break-in what actually happens usually at these situations. And the enthusiasm was really catching. Scalia, who could shake things up on his own, joked as people pass by him on the doorway, "I knew she'd be trouble." And I thought, "Boy, does that take one to know one." But anyway, I used that example to show how Justice Sotomayor, who had spent a lifetime challenging boundaries and disrupting the norm, did it here. And this episode testified to why she was the one who became the historic first, as the first Hispanic at the Supreme Court.

Now I have to tell you when I was talking to the Chief at some moment in a more casual conversation, I let on that I knew about this episode and he was quite put off that I would have been able to recreate it. Because he thought, "Oh my gosh, people have broken all the secrecy." And I thought they were like more than a hundred people there, you can't count on a hundred people not talking to me.

But when I was relating that I thought, because of that, how he reacted to my knowing about that thing at the clerk's party, I wasn't going to tell him what I am now going to relate to you. Which he now knows that I had because I put it in the book. But I almost at that point was going to run up by him to try to get his reaction, but I thought, "If he's so mad that I know about this party, I am not going to tell him about the following." And this is something more substantive that I learned when I was researching the book on Justice Sotomayor. And that was what she did to change the course of what happened in the first version of the University of Texas affirmative action case.

Now this is the case known as Abigail Fisher versus the University of Texas at Austin. Most of you know it in the most recent incarnation when the justices ruled just last June. But there was a first chapter that occurred in 2012 and 2013. Just to refresh your memories this young woman, Abigail Fisher, grew up in the Houston area. She all along had wanted to go to the flagship university in Texas. She had been rejected, her grades weren't strong enough, and she said that it was unfair that the university had a race-conscious program that would allow some students in after a plus factor based on race.

So she loses in lower courts in both rounds as the matter of fact, it gets up to the Supreme Court. And through an unusually long nine months set of negotiations over her case, the justices went from an initial vote to reject the Texas plan and sharply curtail affirmative action to a vote that essentially bought them time. They let the policy stand but sent it back to the Fifth Circuit for further deliberations. And what I found out is that what had ensued was a very tense debate among justices, that initially there was a vote, a majority vote, to send it back, and that Justice Sotomayor had written a very scathing dissent that essentially said, "You don't get it. You justices in the majority do not get it and you don't understand about the continued need for racial remedies."

So as I was talking to the Justices, trying to get this information, and it came interestingly when I was talking to one of them about ... I said something like, "Isn't it interesting that Justice Sotomayor's voice is so heard on racial issues outside the court, because she had become such a speaker about her own personal experiences. But that she hadn't had occasion to write about it yet inside the court." And one of these justices said to me, "Well then, you obviously don't know about what happened in Fisher versus University of Texas." And I thought, "No, I don't."

So then I started nosing around, and it was very, very hard. And one thing I said in my book was that, if you go from just interviews which already are very, very hard to get, of justices of what happens in their private conference and what you can fill in with the blanks. You necessarily only have the story that you're able to get from those key players, you don't have the documents. And I would acknowledge that nobody will know what really happened until you get the draft documents years from now, when probably all of you are gone. And I'm going to of Justices papers, but those can help fill in the blanks.

But it became plain to me when I was able to understand the give-and-take that I was able to get from justices on both sides of the ideological divide that, Justice Sotomayor's draft dissent had caused them to rethink what they were going to do in that moment. Now I should remind everybody that this was back in spring of 2013 when the justices were also issuing the Shelby County decision, which went strongly against civil rights interests in terms of wanting to uphold the 1965 Voting Rights Act in its strongest form. When I started asking justices what Sotomayor's draft actually said they told me to just wait, because it would soon be revealed, in what was then the Schuette case from Michigan.

And for those of you who might remember, there was a 2014 dispute called Schuette versus Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action. And in that one in dispute there was a ban on racial policies in Michigan, including regards to campus admissions. It wasn't like a replay of the gritter and grass decision, it wasn't a replay of the University of Texas at Austin case, but it had enough of a racial dilemma to it.

Justice Sotomayor was on the losing side of that as the court upheld that ban, and she was able to use some of what she had said in that original dissent I saw. And for the first time in her five years on the bench she also took the dramatic step of reading parts of her dissent in the Schuette case from her seat on the bench. And I happened to be in the courtroom that April 22nd 2014 day. Kind of a lucky break because you never know when these decisions are coming down until we get to June.

So what she had done was take some of her sentiment that she had used in draft form in the University of Texas case which had so effectively gotten her colleagues to alter their thinking back then in that dispute, and used it as part of the framing of her objections to where they were going with the shooting case. Schuette case. And in it she complained that the conservative majority simply did not understand how race still inflects daily life for African-Americans and Latinos. And I'm going to quote from her opinion. She said that, "Race matters because of the slights, the snickers, the silent judgments that reinforced the most crippling of thoughts: I do not belong here." She then turned a patented John Roberts phrase against him, and I'm referring to his comment, that the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race. Sonia Sotomayor rejoins the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race.

For his part in that Michigan case, the Schuette versus Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, Roberts rejected the notion that the court majority was "out of touch" and admonished that it "does more harm than good to question the openness and candor of those on either side of the debate." Now interestingly when the University of Texas at Austin case returns to the Supreme Court, last term, Justice Kennedy suddenly was ready to side with the University. And those of you who have followed his jurisprudence on racial issues will probably know that it marked the very first time he had ever voted to uphold such a policy. And I think that Justice Sotomayor's actions bought time for the entire dilemma. And consider what the nation had experienced in terms of racial conflicts since 2013 beginning with the turmoil sparked by the police shooting in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014.

So now that I'm looking specifically at Chief Justice Roberts, I'm tracking the sources of his views on race and other substantive issues. I'm looking for influences from his time as a law clerk to then Associate Justice William Rehnquist, and his time in the Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations. John Roberts was Deputy Solicitor General in the latter administration. And here's another small coincidence, in addition to writing briefs on behalf of the H.W. Bush administration, he was also involved in the screening of judicial nominees. And his paths crossed with Justice Sotomayor who in 1991 had been pushed by then Democratic New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan for a District Court in Manhattan.

Just to give you a little brief aside, we did have a Republican administration in office, it was George H.W. Bush. But in New York there was a Judicial Commission that was sort of made up of both the Republican and Democratic senator. And that was the deal that Moynihan and D'Amato had. Senator al D'Amato had at the time is that Moynihan could also offer nominees. And he had offered to the H.W. Bush administration Sonia Sotomayor, he was the first person who really saw the potential in her. And he even said at the time, I think she could go all the way to the Supreme Court. But John Roberts and the screeners at the time didn't even think she should be on the district court. I think part of it was, it wasn't so much but just what Sonia Sotomayor represented. It was the fact that Moynihan was a Democrat and they're thinking, why do we have to listen to him anyway.

But Moynihan not only was a Democrat, Moynihan was really shrewd about things and Moynihan starts holding up a lot of the Bush nominees for other courts. Including Michael Lunik who was very much on the inside then for the fourth circuit who some of you know who served on the fourth circuit for many years. Moyniham starts holding up action on them and eventually gets Sotomayor through.

But I noted just because was an inauspicious beginning to the relationship of justice Sotomayor and Chief Justice John Roberts. And I think these two justices do epitomize the ideological polarization that was especially evident before Justice Scalia's death. In fact before then, before his February death, studies were showing that the contemporary court was the most polarized in history with a higher percentage of five to four rulings under Chief Justice Roberts under any other previous Chief Justice.

I think his background, notably his politically charged background in the Bush Reagan years, contributes to that and provides a starting point for an explanation of some of those divisions. It's Roberts that his character, his emphases, that the Liberals then react and respond to.

A bit about his personal background. I think that many of you probably remember that, let me see, given where most of you would have been in 2005. But you probably already know his personal background, that's when he was elevated from the DC Circuit to the Supreme Court. He grew up in a traditional Catholic household in Northern Indiana, he is the son of a steel plant boss and a straight-A student. He was captain of the football team. Rather than joined the gritty world of blast furnaces and the steel production though he was the first person in the line who decided to go to law school. He's the first person from his high school to end up going to Harvard. He finished his undergrad at Harvard in three years. He then goes to Harvard Law School. He clerked for Judge Henry Friendly, and then goes to work for as I said then, Associate Justice William Rehnquist.

And then just about the time that he is looking around for what he will do next he hears Ronald Reagan's inaugural speech. And he says that he really felt the call of the Reagan administration. And I think that you see certainly his experience in the Reagan administration in his rulings. He narrowly interprets racial protections as I've mentioned. But he also takes a conservative view on religious boundaries, on reproductive rights. He often expresses exasperation for repeat criminal offenders and those who are dependent on the government.

Now in response the Supreme Court, liberals have become more united and energized, certainly since Chief Justice Rehnquist was in charge. And they've become more adept at navigating behind the scenes. Justice Ginsburg often speaks in private ahead of time to strategize with the other liberals. And I think it's interesting that I brought you back to June 2010, right around the time that her husband Marty had died. And that was the moment when Justice John Paul Stevens, then the senior liberal member of the court was retiring. And he passed the mantle to her to be the senior justice on the left, and I think that has given her a new sense of mission.

When I asked her about that in one interview she said, I know that that's what he would have wanted, referring to her husband Marty. Now of course John Roberts himself is not without conflicts on his own right flank, particularly with Samuel Alito. For example and because of fallout from the Affordable Care Act case. And Roberts constantly engages in a bit of a chess game with Justice Kennedy over control of the court.

And as seen in the Affordable Care Act dispute, the chief is not consistent in all areas of the law. And many cases are decided by unanimous or lopsided votes, but those simply are not the most important ones for the nation. Those are not the most important rulings for the nation. I think among the more defining ones are the Shelby County case, the Citizens United case. Together they enhanced the opportunity for wealthy interests to control the outcome of elections and diminished the ability of minorities to bring voting rights cases.

In that 2013 milestone in Shelby County, which certainly is reverberating today in this election season. John Roberts wrote the opinion that said, things have changed in the south, our country has changed. And I think these days it wouldn't be just those 2013 dissenting justices who would take issue with that. I will close with something that John Roberts said in another high-profile case, the 2015 Obergefell versus Hodges decision, finding a fundamental right to same-sex marriage.

Roberts dissented, and in fact that's when he uttered his first ever dissent from the bench. Now as you know that's a very rare dramatic step that justices take when they want to call attention to their views. And I thought it spoke volumes about John Roberts that he used that occasion, after 10 years to publicly dissent in the fight over gay rights. He said, quote “People of faith can take no comfort in the treatment they receive from the majority today.” He referred to the five lawyers in the majority, dismissively referred to the five lawyers in the majority. And said that they were usurping the legislative processes in the states. And then he asked rhetorically, “Just who do we think we are?” And the question for me as a biographer now of him is, just who does John Roberts think he is? Who is John Roberts?

So when I come back the next time maybe, I will have answers to that. But in the meantime I thought we've got a few more minutes today. If you wanted to ask questions about any of these four subjects, or a little bit about what I've seen since Justice Scalia's death and what might happen in the upcoming term.

Oh, it's always touchy. You don't want to go up to and say “hey what do you think you?” You definitely don't want to do that. No. I have actually two funny stories on that. Justice O'Connor. Now it is tougher when you're writing about somebody who's written a book herself, and Justice O'Conner, the first thing she said to me literally was, how are your sales? It's like she cared. And I of course was not going to put a dent in the Lazy B, which was her book, at all.

So she had to live with me. After I wrote the book I did have another interview with her on something unrelated. My book, this was amazing the timing. I was finishing it up to come out in spring of 2006, but then on July 1, 2005 she suddenly announces she's going to retire. I never worked so hard in my life. In fact compared to law school I remember thinking law school was so hard for me, law school was so hard for me. And then I thought, this is the hardest thing I've ever done. Because I was working full-time. I was working full-time at that moment covering the nomination of John Roberts to be first the successor to Justice O'Connor, and then the successor to Chief Justice William Rehnquist who died about six weeks after Justice O'Connor had made her announcement. Actually she made it July 1, he died on September 3, 2005.

So it was a crazy time and I had to really accelerate that book to get it done, to get it out in '05. We've crossed paths and she'd say, well if it isn't my author. I would not characterize any of them as enthusiastic. They want to tell their story, they don't want me to tell their story.

So then Scalia, Scalia is kind of funny. He at first has said to me, I will not talk to you, you can talk to ... when I was told him I was doing this project. He said, I will tell all my friends, my colleagues, everybody else to talk to you, but I will not talk to you at all for this. And then I ran into him at a wedding, it was strange.

We had a mutual friend who was getting married and I do not run in the justice's circles, I want to make that clear, but we happen to both be at this wedding. And at a wedding you're not carrying this huge handbag and potentially a tape recorder or anything like that, you're just there. And I was there with my husband and I don't think I looked intimidating, and he wants to talk. So he's talking to me and he's drinking, we're all drinking, and I say, Justice Scalia and he was kind enough to ask how my research was going. And I said it's been going great. I said, I'm so impressed with your father who had come to America not knowing any English at all, and then had gotten a Ph.D. at Columbia in Romance languages. And I said, I found a notice in the New York Times about him getting this very prestigious fellowship to go study in Florence and Rome, as part of his Columbia University work. And so I'm telling him things I found out about this family. And Justice Scalia who wants to one up me, he says, yes you found out about that fellowship but did you know I was conceived on that fellowship? And I thought, no amount of research on my part in archives would have gotten me that note.

So then what happened. So this is on a Saturday wedding, he calls me that Monday in my office and he has this wonderful assistant who I love dealing with and she's just great and I just felt for her when he died. She would call me and she'd say, Justice Scalia is on the phone. You'd get on and he'd say, what did you find out about you when my grandpa came through here and all that, because of the family coming over. And I had done a lot of work on the Ellis Island connection with the family and trace back the Sicilian roots.

So he then ends up sitting down with me for 12 on-the-record interviews. Now he had an undisciplined way about him. I do not think Chief Justice John Roberts will do the same thing, at all. So then I go and write the book and then, I wondered how is he going to react and I go to see him on my regular work for Reuters, and he still wants to see me. I'm not writing it for them, I'm writing it for you. I'm writing for all of you and I'm sure they find flaws with it, I'm convinced. But the good thing is they keep talking to me. So that's great.

And then what happened at the end of 2014 after the Sotomayor book had come out, and I had the thing in there about the Texas deal. Now part of it might be they might not read a single thing, but I have a feeling that somebody reads on their behalf. And I had included the Texas case and what had going on in their private conference, and I thought, oh my god now they're not going to talk to me. I wasn't sure. But I needed them for this project I was finishing up at Reuters.

I don't know if any of you had seen, and I think I've talked to you about it. We did this big data project about which private practitioners have the best success at the Supreme Court, what factors do they have in common. And not just look at their oral arguments but their success rate in petitions. And our data people did a fabulous job going through like 12,000 petitions looking through all sorts of lawyers. And I had in the year leading up to this project interviewed talked to them all about this. Eight of them would go on record including retired Chief Justice Stevens. The current chief who knows everything about oral advocacy wouldn't let me put his stuff on the record, but the rest had. But at the end of this project right as the Sotomayor book is out and I'm going on TV and doing radio programs about it, I need to get back with them. And I need to get information to make sure the comments that I'd drawn out from them months earlier were still valid, and I wanted to run the findings by them. And they'd let me all come in and see them, so I was glad about that.

And then that project comes out and they all have issues with that too, pro and con. Mainly they didn't dispute the findings, they were more like, well yes we favor these people. We favor the elite, what's new kind of thing. But then after that came out I thought, oh great, now we'll have a hard time getting in there," but I still been able to get in. Now they bury and I have to say Justice Ginsburg has been especially accessible to me through the years and I've been really happy with that.

I tend to be able to get them to talk to me but there are certain resistances and you have to write a lot of letters, and you have to hope that they understand. That what you're trying to do is to illuminate with this very important public part of government. I think if they had their druthers, I and anybody else who writes about the court, would just sort of fade.

I actually think that it would not cost the court to allow them to be televised in some way. It hasn't cost them in all the oral arguments you can hear at the end of the week. Now I don't think many people are calling them up electronically on Friday. As a journalist I don't really advocate one way or another on it, but I can tell you that a lot of their fears don't seem to be ones that would play out. And it's such a great experience to be in that courtroom.

How many of you have been able to go see arguments? Yeah, I mean really. The majority have not been able to see these arguments and you guys you're it, you're the people they would like to have understand most what's going on there. And it's not like the oral arguments are the rulings, but it does show you the dynamic among these people who are appointed for a life and who are deciding the law of the land. But I do think that they fear the decorum, the kind of decorum that Justice Sotomayor shattered in that salsa thing. They fear that decorum.

And what happens is, like Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan during their confirmation hearings. Both seem very open to the idea of cameras in the courtroom, but then once they get inside they get this cloistered thing and they close ranks against that. Which I think is a real shame for them, but also a greater shame for the public because people should be able to see that. And if it means going to Washington it's just a much more costly venture.

Well it's funny. That's a great question because it is great theater and it goes to your colleagues question there about what people can see or not see. I always describe it as the greatest field trip in Washington. It's so interesting to watch them. And when you're there in the surprise moments when you see a dissent from the bench. As I said, that April day in 2014, I was accidentally in the courtroom. The morning case was the Susan B. Anthony group, the First Amendment case from Ohio. A kind of a smaller case that most of my colleagues didn't even bother going up to because they were waiting for an important set of oral arguments that were going to happen at 11:00.

So I was just helping a colleague by sitting up for the earlier ones. And it was April and we usually don't get our biggest decisions till late May or June. So this really came as a stunning moment to get this great dissent from the bench, so that was memorable. Obviously the end of the 2014-15 term when we had Obergefell and the dissents from the bench, and we had Glossip v. Gross, and I was just telling Rick Hasson about what happened there. Is that that's an important death penalty case that five to three the Conservatives prevail in. Justice Breyer takes the occasion to read a dissent from the bench about how the court should really reconsider its death penalty jurisprudence, that there's just too much arbitrariness and potential problems in terms of discrimination.

And then Justice Scalia, out of the blue, gets so angry and provoked that he starts to dissent from the dissent. And not only that, it was the death penalty case that they were on that day. But then he says, “And I also want to tell you why I still don't like the gay marriage ruling." So it was one of those moments that you hope was completely captured on tape that people can eventually hear, but it would been important for and interesting for people to see.

So that was good. And I was there during Bush v. Gore and that was exciting, and so I have a lot of them. One thing with me when I'm writing books, I do tend to find everything very interesting and I have to figure out, okay what is not just interesting, what is not just a little chestnut here, but what's important.

Okay. This is interesting. I was talking to one of your professors who does lawyering skills, and it wasn't Henry. It was somebody else. And we were talking about the art of interviewing and just what you need to do when you're interviewing witnesses and when you're interviewing anyone for your daily work. And it isn't unlike what journalists often do.

I spend a lot of time thinking out my questions, I write them down. I always write down questions before I go in, knowing what I want to know. I try to figure out transitions, I try to be prepared for anything, and I always tape record. Because in the moment you might not really be hearing something, and because you're thinking ahead so you just work it in every way. And the other thing is you go back as often as you can possibly go back. It's hard to get in there in the first place but you just keep trying to go back, trying to go back. And you try to convince them which is the truth that, even though they might not like things and even though we all make mistakes here there. We all have flaws in what we do. That what I'm trying to do is establish the reality of the record, and what is actually happening and who they actually are.

So you're trying to get at something and from where I sit I am still mainly a journalist, I don't go into these things with an agenda. It's not the kind of writer. So you try to convince them that you're an honest broker and that they will respond in kind. Okay. One last one and then I'll let everybody go for the hour.

Actually I think what's going to happen is that, we're in this seismic shift because the absence of Justice Scalia just changes the balance completely. The highest probability is that Merrick garland will get on the court, probably not by the end of the year but maybe in the next administration. If he gets on the court first of all he's not adding all that much diversity although he would bring in as another Jewish justice, but it would be five Catholics and four Jewish justices.

I don't think the polarization is in their identities, their demographics. I think the polarization is flat in the ideologies. Now if that's some of their back their background feeds those, but I think that what we'll see is obviously suddenly the left is going to have the upper hand in a way that it hasn't had for decades. I think this is the most challenging moment that John Roberts has faced in his professional career and it'll be really interesting to see how he navigates this. But I think you're going to see a lot of struggles, and it won't be so much with Justice Kennedy anymore, it will be probably with the most conservative of those on the Left. Who might be Justice Breyer or maybe a justice Garland, or whomever.

So let's hope, let's see what month are we in? I can't imagine that we'd go another six months. I mean we've gone, now what, it was February 13, what are we on today? The 14. So we've gone since February 13 with an 8 member Court. I think it's highly likely we're going to go several more months with an 8 member Court but, I can't imagine that next year at this time when the Supreme Court's opening we wouldn't finally have 9 members. So thank you all.

[Narrator] Thank you for joining us for UCI law talks, produced by the University of California, Irvine School of Law.